Learning About Hurricanes

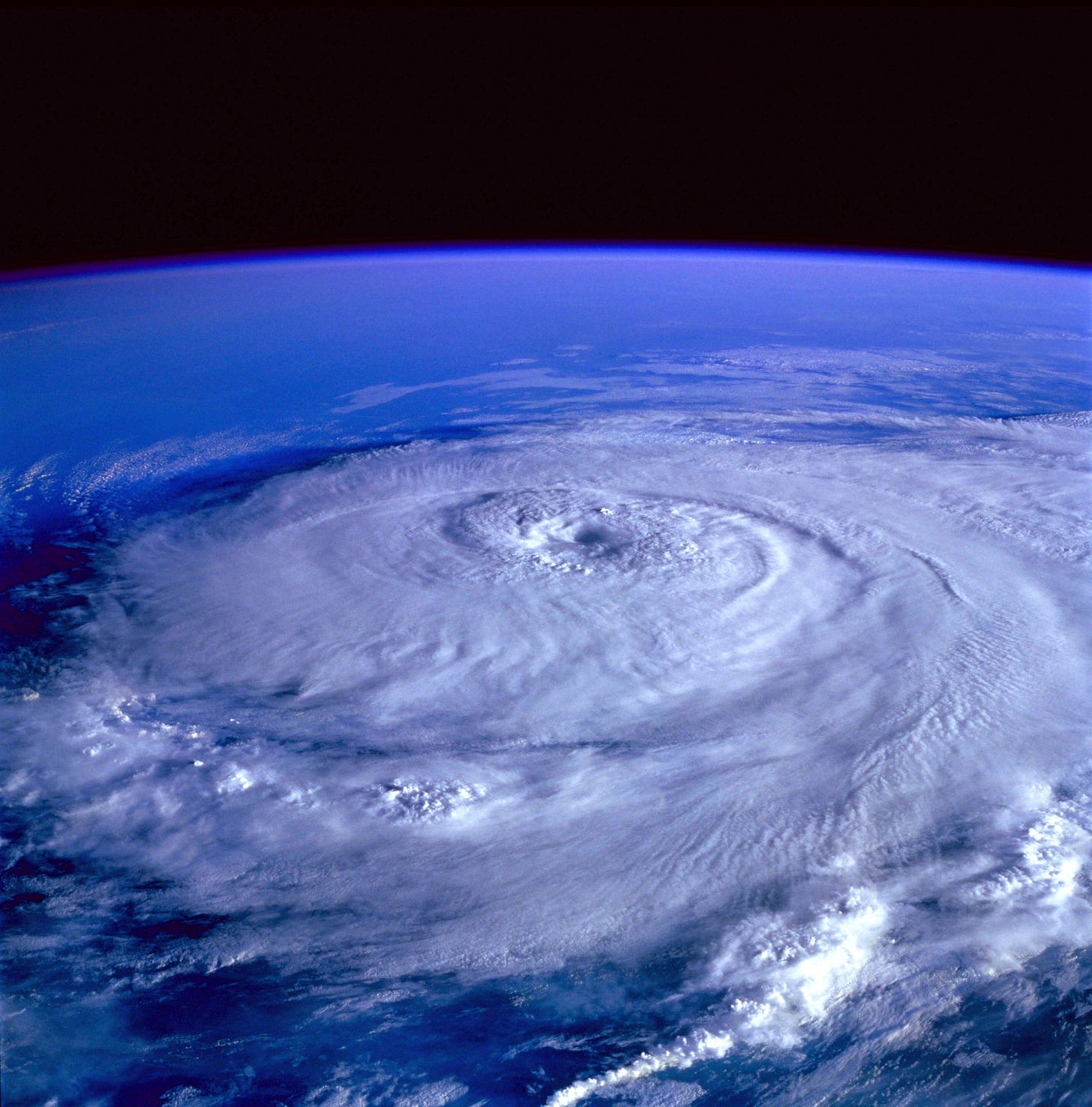

How do hurricanes form, how are they classified, and what does the future look like?

Hiya!

I've lived my entire life in the Pacific Northwest, which is known for its wildfire zone, so I'm less familiar with storms like the hurricanes the East Coast experiences.

I’ve never personally experienced a hurricane except for sharing a name with Hurricane Katrina hurricane which ravished New Orleans in 2005. It struck my first year of college when everyone was making friends and learning names. I still get hurricane references when I introduce myself, it actually happened yesterday.

Anyway, it’s high time I learn about hurricanes especially considering the recent events involving hurricanes Fiona and Ian. And wow, hurricanes are truly terrifying yet awe-inspiring, powerful storms—and it appears they’ll only become even more so in the future.

How Hurricanes Work

According to NASA, only four things are needed to create a hurricane — lots of moisture in the air and warm ocean waters, a pre-existing disturbance such as a cluster of thunderstorms, and a low vertical wind shear.

If you're like me and have never heard of a "vertical wind shear," it's the changes in wind speed and/or direction that occur within a vertical shaft from the ground to the atmosphere. Such as the changes in wind conditions for the height of a hurricane.

NASA uses a tower made of blocks as an example, like the game Jenga. If you push the top and bottom of the block tower across the table using the same strength and in the same direction, then the tower is likely to stay intact as it travels — this would be considered low vertical wind shear, which is needed to form a hurricane.

Whereas if you pushed the top and bottom of the block tower using different strengths, and moved them in different directions, then the tower would topple. This is known as high vertical wind shear, which limits a hurricane's strength and can even stop it altogether.

Hurricanes form over the oceans and are notoriously difficult to predict since their actions depend on the large-scale weather movements around the storm—which we have a challenging enough time deciphering even without a hurricane.

Basically, hurricanes are giant, revolving thunderstorms (I know they’re awful, but that’s pretty amazing) that form over subtropical and tropical warm waters with low circulation levels. Once a tropical storm’s winds reach 75 mph (121 kph), they become classified as a hurricane—and then the sky's the limit (literally) in how fast its winds can grow.

Categorizing Hurricanes

In the 1970s, engineer Herbert Saffir and meteorologist Robert Simpson devised a scale to estimate the likely effects of hurricanes on any given area. It's called the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, and as its name suggests, it largely depends on the speed of hurricane winds.

Admittedly, the scale isn't perfect, but it's still used today as a 1 through 5 system for measuring hurricanes. Though the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) website warns visitors that it "does not take into account other potentially deadly hazards such as storm surge, rainfall flooding, and tornadoes." Still, here's a screenshot from their site of the scale.

For reference,

Hurricane Fiona hit southwestern Puerto Rico as a Category 1 with 85 mph (140 kph) winds. By the time it reached Turks and Caicos, it grew to Category 3, and by the time it got to Canada, Fiona Peaked at Category 4 with winds of 115 miles (185 kph).

Hurricane Ian, however, hit Florida's Gulf Coast with raging 155 mph (249 kph) winds making it just shy of a Category 5 hurricane — of which there are only five in the United States’ recorded history — then Ian hit North Carolina after dropping to a Category 1 which can cause significant damage.

Speaking of damage, it'll be a bit before we have a complete picture of the damage done by either recent hurricane. But we do know the outcome of Hurricane Katrina is considered one of the most destructive and financially costly natural disasters in U.S. history.

Hurricane Katrina flooded 80 percent of New Orleans, killed at least 1,833 people, and inflicted approximately $108 billion in damages. The storm was classified as Category 1 when it landed on the southeast Florida coast with 80 mph (129 kph) winds. But it strengthened to Category 5 status—with peak sustained 175mph (282 kph) winds— as it traveled to the Gulf of Mexico's warm waters.

Global Warming is Influencing Hurricanes

Tom Knutson, NOAA's senior scientist in their Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, cautions that "even if hurricanes themselves don't change [due to climate change], the flooding from storm surge events will be made worse by sea level rise." Knutson also predicts heavier rain when the storms hit land, leading to significantly more flooding and damage.

A 2019 paper found that since the 1980s, on average, there's been more storms in general, with stronger hurricanes and more hurricanes that intensify quickly. However, they state most of these escalations appear to be caused by natural reasons… until recently. They suggest the number of North Atlantic hurricanes experiencing rapid intensification is a bit too large to be natural and that we could be at the beginning of witnessing the impact climate change can have on storms.

Researchers from the University of Madison-Wisconsin and NOAA’s National Center for Environmental Information came together and published a much more recent study in September 2022 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

They found that while temperatures are usually the hot topic when it comes to global warming, and for good reason, we should also be looking at the outcome of the rising global temps. Warmer temperatures mean hurricanes have more energy to grow stronger over time.

So far, this strengthening of hurricane winds is happening in nearly every area of the planet known to give rise to such destructive storms. Not to mention, stronger hurricanes aren't the only disastrous outcome of rising temperatures. Another recent study discovered that:

Of 375 human diseases, we found that 218 of them, well over half, can be affected by climate change.

So… that’ll be fun.

Perspective Shift

We like to reference things like outer space, the ocean, and mountains as humbling examples reminding us just how tiny we are in the grand scheme of things. But it seems as though storms as large as hurricanes — so massive and dangerous that we name them — may serve as even more important reminders of our inconsequence in the grand scheme.

Actually, perhaps idolizing the stars and seas as monuments too great for us to impact played a role in getting us into this mess. We assumed such things were too large and wonderous to be harmed by our seeming unimportance, but we were wrong. Humans may be physically tiny compared to the ocean or a hurricane, but our impact is anything but insignificant.

Thankfully, part of growth means acknowledging our ignorance and mistakes, then correcting future behavior. We know now the effect we have on the planet and many (though probably not all of) the choices that got here. Our influence doesn't have to be harmful, and it's not too late to turn things around. We are small but brilliant, resourceful, and creative. All it'll take to correct our path is to shift our perspective to one focused on finding solutions.

Just as a reminder, you’re currently reading my free newsletter Curious Adventure. If you’re itching for more, you’ll probably enjoy my other newsletter, Curious Life, which you’ve already received sneak peeks of on Monday mornings.

Any payments go toward helping me pay my bills so I can continue doing what I love — ethically following my curiosities and sharing what I learn with you.

You can find more of my writing on Medium. If you’re not a member but want to be, click here to sign up! Doing so allows you to read mine and thousands of other indie writers to your heart’s content.

Lastly, if you enjoy my work and want to show me support, you can donate to my Ko-fi page, where you can also commission me to investigate a curiosity of your own! Thank you for reading. I appreciate you.