Microbes Inherit Memories

Researchers discovered bacteria learn to evade antibiotics using memories from previous generations

Hiya!

Believe it or not, but the concept of teeny-tiny microbes having some form of memory has become widely accepted, with plenty of research supporting it. Some studies even found that memory shapes microbial populations. Scientists haven’t understood how it works, but new research is beginning to change that.

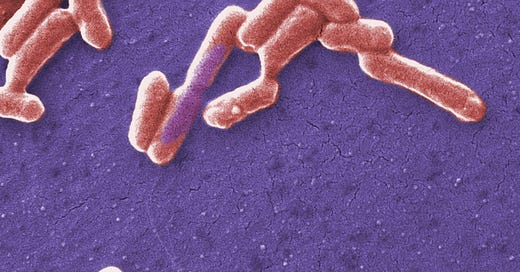

Microbiologists recently found that E. coli bacteria use iron levels to store information. Further, the bacteria “remember” specific experiences for at least four generations, and the swarming behavior they engage in essentially conditions the bacteria with the memory.

Microbial Swarms

We may imagine microbes, like bacteria, as tiny single-celled organisms that mindlessly scurry around, doin’ their own thing. But in actuality, bacteria work together. Similar to how honeybees relocate their hives, bacteria collect into colonies called swarms that travel collectively in search of a permanent home. And, like for so many other life forms, there’s power in numbers.

Forming swarms helps bacteria increase their cell density, making them better able to withstand antibiotic exposure — something microbiologists like Souvik Bhattacharyya of the University of Texas in Austin are particularly interested in. Even more so after he observed swarming Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria form what he called “weird colony patterns,” he’d never seen before.

Bhattacharyya then isolated individual bacteria to observe their behavior and found it differed based on their past experiences. Bacteria cells from previously swarmed colonies were more apt to swarm again than those that hadn’t.

Even more surprising is that the offspring repeated the behavior for at least four generations — around two hours. So, understandably, Bhattacharyya and his colleagues wanted to figure out why this was happening.

Microbial Memory

The idea of microbes having memory, in any form, might seem a bit off for the simple reason that they don’t have brains. But that just means their memories work differently than ours. Bhattacharyya says microbial memory is more like information stored on a computer. He explains:

“Bacteria don’t have brains, but they can gather information from their environment, and if they have encountered that environment frequently, they can store that information and quickly access it later for their benefit.”

For their new study, published in November 2023 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the UT-led research team tweaked the E. coli genome and discovered two genes that control iron regulation and uptake. If you don’t know, iron is the fourth most abundant element on Earth, making up about 5 percent of our planet’s mass. Bhattacharyya explains in a news release:

"Before there was oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere, early cellular life was utilizing iron for a lot of cellular processes. Iron is not only critical in the origin of life on Earth, but also in the evolution of life. It makes sense that cells would utilize it in this way."

The scientists observed that bacterial cells with lower iron levels seemed predisposed to be better swarmers, which, the researchers believe, could allow these swarms to search for new locations with ideal iron levels.

Meanwhile, the bacterial cells with higher iron levels were more likely to form biofilms — sticky, dense mats made of complex bacterial communities living on solid surfaces. If swarms are communities of bacteria, biofilms are bacterial cities. Lastly, the team found that the iron memories lasted for at least four bacterial generations and disappeared by the seventh.

The scientists theorize that lower iron levels trigger bacterial memories to encourage microbes to form a swarm and seek iron in the environment. In comparison, higher iron-level memories suggest the swarm is in a good environment, so the bacteria should stay and multiply by forming a biofilm.

Perspective Shift

Can we take a moment to consider how remarkable it is that we’re living during a time when scientists can learn such incredible things about some of the smallest organisms on the planet? Of all the things to discover about these tiny lifeforms, the fact that they have memories — of any kind — is astounding.

If even the smallest organisms have memory, even rudimentary, might this also mean they possess some form of consciousness? Some research suggests the answer just might be yes. The concept of panpsychism definitely says yes.

Regardless, the fact that bacteria pass these memories down through generations reminds me that we aren’t so different. Back in 2022, we learned that generational trauma (and healing) can be passed down thanks to epigenetics. So, if tiny life forms like bacteria and larger life forms like us humans both inherit information from previous generations, whether memories or experiences, what about other animals? Just how widespread is this phenomenon?

Just as a reminder, you’re currently reading my free newsletter Curious Adventure. If you’re itching for more, you’ll probably enjoy my other newsletter, Curious Life, which you’ve already received sneak peeks of on Monday mornings. The subscription fee goes toward helping me pay my bills so I can continue doing what I love — following my curiosities and sharing what I learn with you.

You can find more of my writing on Medium, where you can read mine and thousands of other indie writers to your heart’s content.

Lastly, if you enjoy my work and want to show me support, you can donate to my PalPal or my Ko-fi page, where you can also commission me to investigate a curiosity of your own! Thank you for reading. I appreciate you.

Very interesting, and logical. Clicking on the panpsychism link led me to your 2022 article. Another good one! I love how your newly discovered scientific revelations confirm many of my intuitive perceptions. Everything is linked, and everything deserves respect.