The Central United States is a Climate Warming Hole

The region is experiencing far less global warming fluctuations compared to the eastern and western areas of the country

Hiya!

Weather is notoriously challenging to predict. Even with today’s advanced technology, meteorologists’ predictions lose accuracy after a few days — and global warming only makes the weather even more unpredictable. These days, accurately predicting weather patterns has gone from the mundane to sometimes life-or-death decisions — like whether to evacuate or prepare for a significant climate event.

We thought we understood pretty well how the climate works, but global warming shows us how little we really know. However, the increase — both in frequency and intensity — of extreme climate events also illuminates strange areas, not because of any severe weather but because of the absence of it.

Warming World

The science is in, and it overwhelmingly shows that global warming is real, and it’s already begun. In 2015, country leaders gathered at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP21), where they created the Paris Agreement with the shared goal of limiting global temperature rise to 2°C (35.6°F) below preindustrial temperatures and then try to keep global temperatures to no more than 1.5°C (34.7°F) above preindustrial levels.

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) states:

“Since 2015, 197 countries—nearly every nation on earth, with the last signatory being war-torn Syria—have endorsed the Paris Agreement. Of those, 190 have solidified their support with formal approval. The major emitting countries that have yet to formally join the agreement are Iran, Turkey, and Iraq.”

As of this year, eight years since the Paris Agreement, global temperatures have already increased by 1.1°C (33.9°F) above preindustrial standards. That said, it’s important to remember this is an average global temperature, and its effects overlap with Earth’s natural climate systems.

This means some areas of the planet are warming much faster than others — such as the Arctic, which is warming four times faster than anywhere else — and some years will be warmer, wetter, drier, or colder than others.

Yet, experts are noticing areas that stand out, not because the weather is growing increasingly chaotic, but because it’s not. One such place is in the central United States, a region that appears practically untouched by the growing intensity of global warming.

The Warming Hole

Unlike the eastern and western parts of the United States, the daytime summer temperatures of the central U.S. have barely warmed since the mid-20th century. Scientists refer to this area as the “warming hole.”

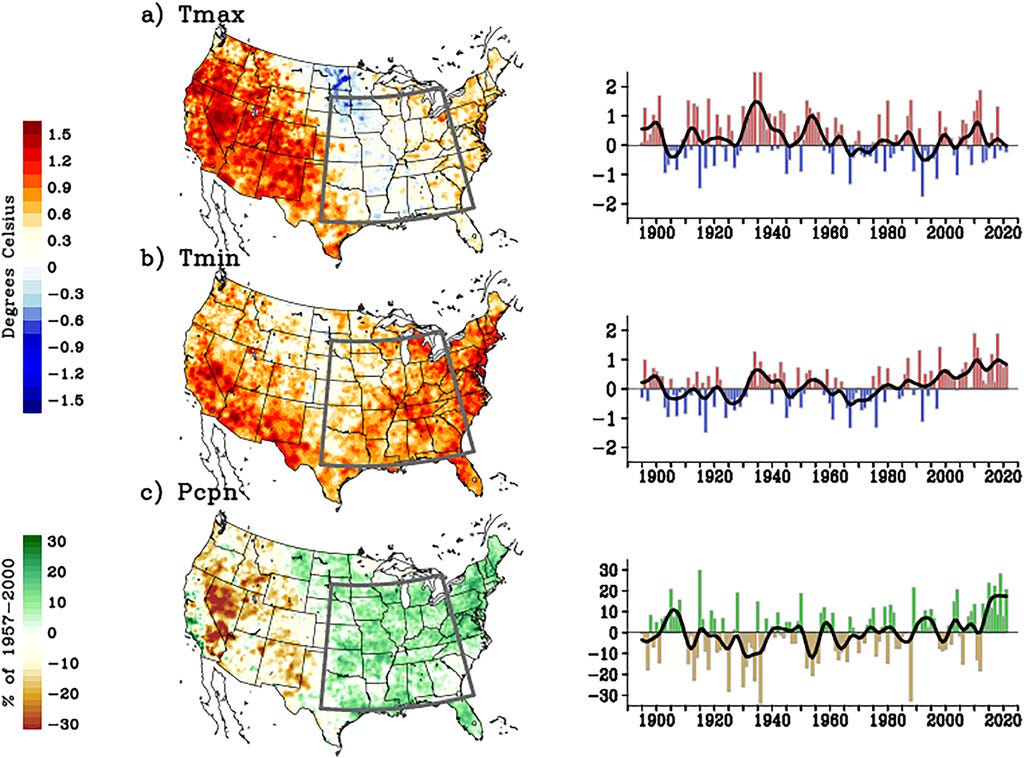

The image above comes from a research paper I’ll tell you about in a minute, but it shows where the warming hole is, as outlined in the grey box. Maps A and B show maximum and minimum temperatures between May and August between 2001 and 2020, compared to the same months between 1957 and 2000.

There were no changes in white areas — such as Illinois, Arkansas, and Missouri. The blue spots in Minnesota, Iowa, and the Dakotas are where temps actually fell, while the red areas, like pretty much the entire western states, are where temperatures rose.

The bottom map shows the precipitation levels between the two time frames. As you can see by the green coloring, the warming hole got quite a bit more rain than anywhere else.

Previous research on the warming hole using data through 1999 suggested natural internal climate variability created the warming hole, and it would likely disappear. Yet, it remains despite increasing global warming events all around it. Martin Hoerling, a climate scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), explains:

“There’s a significant population that lives and works in this part of the US that scratches its head and says, ‘What’s all this fuss about climate change?’ It’s very counterintuitive, because global warming has accelerated while the warming hole has continued.”

Hoerling, along with Zachary Labe, a climate scientist at Princeton University and NOAA, and their colleagues believe that since the warming hole is still here, it’s time to reexamine the phenomenon and seek alternative explanations for what’s causing it. They recently published their findings in the Journal of Climate.

Intriguingly, based on their research, it doesn’t seem global warming has merely forgotten about the central U.S. but may be partly responsible for the mild climate bubble.

How is it Happening?

Naturally, scientists have all sorts of theories to explain the warming hole and why it has persisted for so long. Many of which Hoerling and Labe discuss in their paper.

One theory suggests aerosols in the atmosphere above the region reflect some of the sun’s energy into space, cooling the daily temperatures in the area. Another theory proposes the land “sweats,” much like our bodies do. More specifically, the irrigation used to support agricultural farmlands throughout the central U.S. helps cool the area from the ground up.

After weighing the evidence, Hoerling and his colleagues lean toward the latter. They agree water could be cooling the central U.S., but they have a slightly different theory. Labe explains:

“There still potentially could be effects from agriculture, but we found this warming hole to be bigger than the agricultural change. We think it’s more likely linked to some sort of atmospheric condition.”

In their paper, the scientists point out that summertime precipitation has dramatically increased across the central U.S. over the last twenty years compared to between 1957 and 2000. Remember the last map in the image above showing precipitation? It shows a 30 percent increase in rainfall. As a result, the increased water on and in the landscape would function as an evaporative cooler.

The increased precipitation likely results from the lower-pressure system common over the region. Labe explains:

“Low pressure is associated with stormy air conditions, so more rainfall, more cloud cover. You can think of that as dampening the amount of warming that can be possible during a hot afternoon.”

Clouds make perfect deflectors. The denser they are, the more of the Sun’s energy they reflect back into space. Water helps keep an area cool by acting as a sort of buffer. When the sun shines on wet ground, it has to evaporate the precipitation before it can heat the soil.

So, the warming hole may be a mixture of natural climate variability and global warming — and the increased precipitation caused by it — could explain why the warming hole hasn’t succumbed to the warming effects of the areas around it. Yet.

Matter of Time

While the warming hole has preserved longer than experts first expected, Hoerling and Labe say it’s just a matter of time before the region begins reflecting the rest of the country. Labe explains

“We looked into the future and found [that] essentially by 2040, 2050 … the probability of Dust Bowl–like extreme temperatures will become very much more probable [in the central U.S.].”

Meanwhile, Hoerling cautions:

“That’s part of the warning of this paper. That this coolness is probably still rather transitory.”

If current climate models are correct, summertime heatwaves and heat domes will only become more frequent and intense as time goes on. So, while the central U.S. has had a slower start compared to other areas, it’s not likely exempt from experiencing more extreme global warming events in the future.

Perspective Shift

As global warming decimates cities and countries, more people will seek new areas to live that are safer than wherever they’re coming from. This is called climate migration, and millions are already doing it each year. For now, the warming hole seems a bit like a climate-safe haven, a little bubble of protection from the extremes of global warming. But if Hoerling and Labe are correct, it won’t likely stay one for much longer.

There aren’t many upsides to global warming, but you gotta admit, we’re learning a ton about our planet because of it. The urgency global warming puts on us to radically understand the planet’s climate systems, our role in disrupting those systems, and strategies to lessen our impact are paramount, and future generations depend on it.

Just as a reminder, you’re currently reading my free newsletter Curious Adventure. If you’re itching for more, you’ll probably enjoy my other newsletter, Curious Life, which you’ve already received sneak peeks of on Monday mornings.

The subscription fee goes toward helping me pay my bills so I can continue doing what I love — following my curiosities and sharing what I learn with you. You can find more of my writing on Medium, where you can read mine and thousands of other indie writers to your heart’s content.

Lastly, if you enjoy my work and want to show me support, you can donate to my PalPal or my Ko-fi page, where you can also commission me to investigate a curiosity of your own! Thank you for reading. I appreciate you.